Building fairer cities

I had the pleasure of joining the panel at the World Car Free Day Summit to share my perspectives on how we build back more equitable cities. Specifically to look at some of the successes in decarbonizing transport that have been achieved by the city of Montreal – where my team and I are extremely proud to be a part of a growing collective of transport planners; looking to understand the ways in which different transport users move, how places can become better connected and more accessible and how prioritizing sustainable transport modes and alternatives to the car can mitigate the huge impact of emissions felt on society.

Avoid, shift, improve

A way to categorize the changes being made to decarbonize transport is through the “avoid, shift, improve” framework.

Simply, ‘avoid’ encompasses changes which remove or reduce the need for transportation. This comes with denser cities, transit oriented development (TOD) and compact neighborhoods, such as those championed through the 15-minute city concept. ‘Shift’ moves us towards investment in public transport, walking and cycling infrastructure, and managing parking provisions in city centers. Finally, ‘improve’ introduces electrification and cleaner vehicles, for example.

Our experience is that governments tend to place a focus on the ‘improve’ part – avoiding (or at least de-emphasizing) ‘avoid’, which is in fact the most efficient way to decarbonize transport through a fully-integrated planning approach that generates less need for transportation in cities.

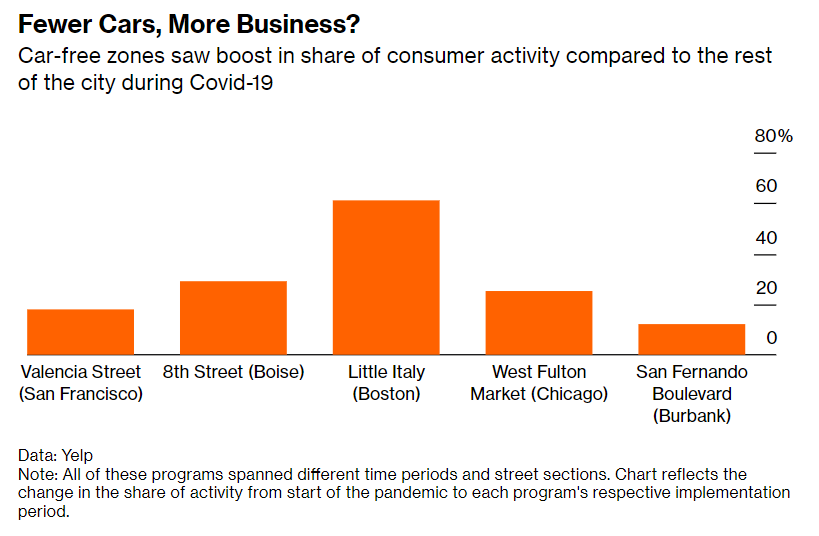

Effect of car-free zones on business in cities around USA. [1]

Montreal adopted its sustainable plan in 2016 and Valérie Plante, mayor of Montreal, last year announced an intention to reduce emissions by 55% by 2030. Clearly this is a huge target and several transport initiatives are already underway, happily spanning the three areas of our avoid, shift, improve framework.

Over the last decade Montreal has taken a transit-oriented approach to developing new neighborhood plans through a bespoke planning guidance tool. This allows for transport and land use planning to be integrated into the whole neighborhood from the outset. A great example of this is the new University of Montreal campus, which will be mixed use reconnects the area to the metro via a new pedestrian and cycling bridge. The result will deliver a whole neighborhood, within the existing fabric of the city, integrated through active transportation.

Montreal has also considered ‘shift’ – setting a major target to double cycling infrastructure. We’ve seen lots of project delivery in this area already with express cycle lanes being built, and very recently, active cycle lanes arriving as a result of Covid-19 and our changed needs. With the introduction of these active cycle lanes we’ve seen a growth of 36% in people cycling on Montreal’s streets this summer. A pilot micro consolidation center project was also launched last year, aiming to cut the number of deliveries made and moving deliveries from goods vehicles to cargo bikes for the ‘last mile’ to the city center.

Wellington Street, Verdun, Montreal [2]

Finally, plans for electrifying transportation were adopted by the city in 2016. The municipal fleets will convert to electric; charging point will be installed and we will see electric buses on our roads. Whilst these ‘improve’ measures are welcomed, we know that they’re the least efficient in decarbonizing a city – and what’s more electric vehicles still produce traffic jams!

Challenges to decarbonization

Although the city is being innovative, it also faces key challenges in its move to a more efficient transport decarbonization, which equally apply in cities across continents.

Firstly Montreal faces different scales of governance through its governance model: planning law is provincial, planning applications are dealt with at the borough scale and the metropolitan area of Montreal has limited planning powers to really deliver the revolution needed for transport decarbonization. Similarly transport is financed by the provincial and federal governments. And last, and perhaps the most engrained and complicated challenge, the model of social sprawl and how we as planners design connected spaces that are attractive to the types of people who traditionally move to the suburbs for more space and more comfortable lives.

But, as I celebrate nearly three years in Montreal I have reason for optimism. I’m encouraged by the strides that are being taken here and – importantly – the message that with political leadership and the will to achieve decarbonization goals, the same can happen anywhere across the world.

[1] Bloomberg CityLab, “Where Covid’s Car-Free Street Boosted Business“, Laura Bliss, 11 May 2021 : https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-05-11/the-business-case-for-car-free-streets?cmpid=BBD051121_CITYLAB&utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter&utm_term=210511&utm_campaign=citylabdaily

[2] Cission, “COVID-19: Verdun aménagera 21,5 kilomètres de voies sécuritaires au profit des piétons cyclistes , et commerçants“, Ville de Montréal – Arrondissement de Verdun, 28 May 2020 : https://www.newswire.ca/fr/news-releases/covid-19-verdun-amenagera-21-5-kilometres-de-voies-securitaires-au-profit-des-pietons-cyclistes-et-commercants-832625512.html