What’s next for Transit-Oriented Development in Canada?

Transit Oriented Development (TOD), be it around a rail, underground, light rail, tram, or bus rapid transit line, has been a cornerstone of urban revival for the last decades. It is a remarkably simple idea: if people and urban activities are concentrated around key transit hubs, then users would choose not to travel by car. Even before cars, it is around the early concepts of TODs that modern mass-transport systems were developed. While the idea faded during the car boom of the second half of the 20th century, preferring sprawling suburbs and retail parks, the concept was then recovered in search of a more sustainable urban form and was broadened to include communities that promote economic vibrancy, and seek to densify existing neighbourhoods.

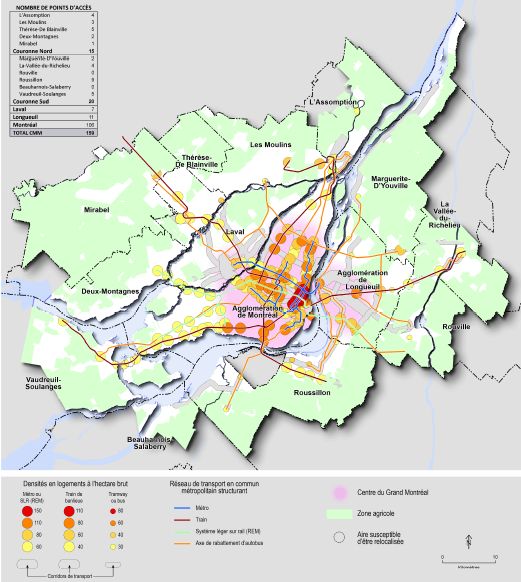

In Montreal, the concept of TODs was embedded into our planning framework in 2011, with the development and publication of the Plan métropolitain d’aménagement et de développement (PMAD), by the Communauté métropolitaine de Montréal. This document sets forth guiding principles for the sustainable development of the Greater Montreal Area (GMA), which need to be considered in every municipality and borough’s urban development plan. The CMM requests that 60% of the GMA’s future growth be located within 1 km of a metro, train, or light-rail transit station, or within 500 metres of a tramway, bus or bus-rapid transit station, and sets minimum density thresholds for these areas which are illustrated in Figure 1.

Rider density in public transit has become a significant concern due to the COVID pandemic. As long as social distancing measures are in place and as long as COVID threatens our health, relying on mass transit to service high-density developments is very difficult. The psychological impact of this disease casts significant doubts on the appetite to return to crowded urban areas.

Although probably inevitable in the short term, walkable and transit-oriented neighbourhoods should not allow a car-based recovery to stop the sustainable urban and mobility regeneration momentum. Emerging urban development models, such as the 15-minute city developed in Paris, favour human-scale neighbourhoods that focus on sustainable mobility. This model is “based on four major principles: proximity, diversity, density and ubiquity, […] individual areas within the city should be able to fulfil six social functions: living, working, supplying, caring, learning and enjoying”[2].

As lives have become more local during the lockdown, this urban development model could very well be the future of TODs. This model does not focus solely on high- (or hyper-) density, heavy mass transit infrastructure and utilitarian linked trips. The 15-minute city is a holistic approach that takes into account work-life balance, social and family interactions and the dissemination of economic opportunities across metropolises, towns and cities, rather than in small, often (economically and socially) inaccessible clusters.

While we look at making these clusters accessible, we should be aware that the boundaries between neighbourhoods can become barriers, often creating social segregation. The design of these boundaries should allow for urban creativity while ensuring connectivity between areas. In a conference for the Department of International Trade, Metrolinx, the transport agency running the Greater Toronto and Greater Hamilton areas, raised some concerns regarding travel patterns post-COVID. If remote working remains common practice, Metrolinx foresees an increase in commutes between outer regions, rather than towards the downtown core. For them, maintaining a healthy tension between GO Transit, the regional public transit system, and each municipality’s transit operator will be key.

In the same conference, the City of Edmonton discussed the current deployment of its Light Rail Transit system. Similar to the 15-minute model, Edmonton’s City Plan defines areas that can be accessed through 15-minute trips and targets them for development and growth. Approaches such as these can ensure that segregating boundaries between neighbourhoods can be easily overcome.

Once the more immediate threat and fear of the contagion subside, we might find a clue to the future of transit-oriented developments in this tension between planned centres and informal edges, as they move from transit-oriented developments to sustainability- and inclusivity-oriented communities.

[1]Reproduced from Communauté Métropolitaine de Montréal, 2011. Carte 7 – Les aires TOD – Seuils minimaux de densité résidentielle.“https://cmm.qc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/C07_PMAD_Aires-TOD_2018-01.pdf”

[2] Kim Willsher, The Guardian—Paris Mayor unveils ’15-minute city’ plan in re-election campaign, 7th Februray 2020